In freshwater fly fishing, a nine-foot-five-weight has become the default beginner’s fly rod. This isn’t without some merit, and it’s pretty hard to go wrong with a nine-foot-five-weight rod. But that doesn’t mean that a seven-foot-four-weight (or something else) wouldn’t serve you just as well, if not better. As you will quickly learn, there is almost always more than one way to approach the fly fishing we do; none of which are necessarily “wrong.” But there are those that will disagree with that statement, and try to convince you to spend your money for this, that, and the other thing. And so it begins…

The Rod Designer, the Professional Guide, the Fly Shop Owner, the Sales Rep, and definitely the Blogger (like myself) all have an opinion on what you should buy as a first time fly fisherman, and those opinions are likely based upon some facts and hard earned experience. As such, those opinions probably shouldn’t just be ignored. But therein lies the problem a beginner is faced with in selecting equipment: They get wildly differing (and often conflicting) opinions from people “who know,” so who’s right? The truthful answer is, they all might be. Which is not very helpful to you is it? So let’s go a little further and see if we can clear the fly fishing waters a bit.

There are some aspects of fly fishing that are beyond opinion, and are simply realities of the natural world we live in. The laws of physics for example don’t suddenly change just because we pick up a fly rod. Gravity still exists. The laws that govern momentum and inertia still apply, as do those principles of volume and area. So regardless of anyone’s opinion, these laws simply can’t be changed or circumvented, and they should be used to provide the basis for selecting fly fishing equipment regardless of your skill level. Which is why I also happen to believe that the very first thing anyone should determine when choosing new fly fishing equipment is this: What fly sizes do you typically want to use with this rod? (You don’t even have to choose the exact flies, just the typical sizes.)

The answer to that question provides the foundation for every other decision that must be made in selecting equipment. And one of the greatest things about this question is, it’s probably the least “glamorous” decision you will make, and it suffers from little (if any) influence from biased sources or opinions.

The fly sizes you want to use will be based upon the type of fly fishing you intend to do (Dry Fly, Nymphing, Streamers, All Around, etc.) and the intended quarry you are targeting. (Trout, Bass, Pan Fish, Bonefish, Tarpon, etc.) So it’s usually a pretty easily obtained and straight forward set of parameters to work within and there won’t be much debate about what size flies are appropriate.

Once the range of fly sizes is determined, you have established a clear physical attribute for the fly fishing you will do. In other words, you have defined one variable in any law of physics that applies. And since fly lines are designed (at least in part) with those laws of physics in mind, you now have an easy way of determining what fly line weight rating you should select.

It doesn’t take a physics expert to understand that a smaller fly is (generally speaking) lighter than a larger fly. It’s also easily understood that given the physics used to cast a fly line (see my post Why Fly Fish) a heavier fly line is needed to efficiently cast a heavier fly. And while an even heavier line could be effectively used to cast the same fly, at some point the fly line’s weight (and size) becomes a negative attribute to gently landing on the water. For some types of fly fishing this may not matter much. But for dry fly fishing it certainly does. Again, physics are at play here, not opinion. It is simply a fact that the heavier (and fatter) the line, the “bigger the splash.” So for dry fly fishing, the trick is to use the lightest line weight that will still efficiently cast the typical fly size being used.

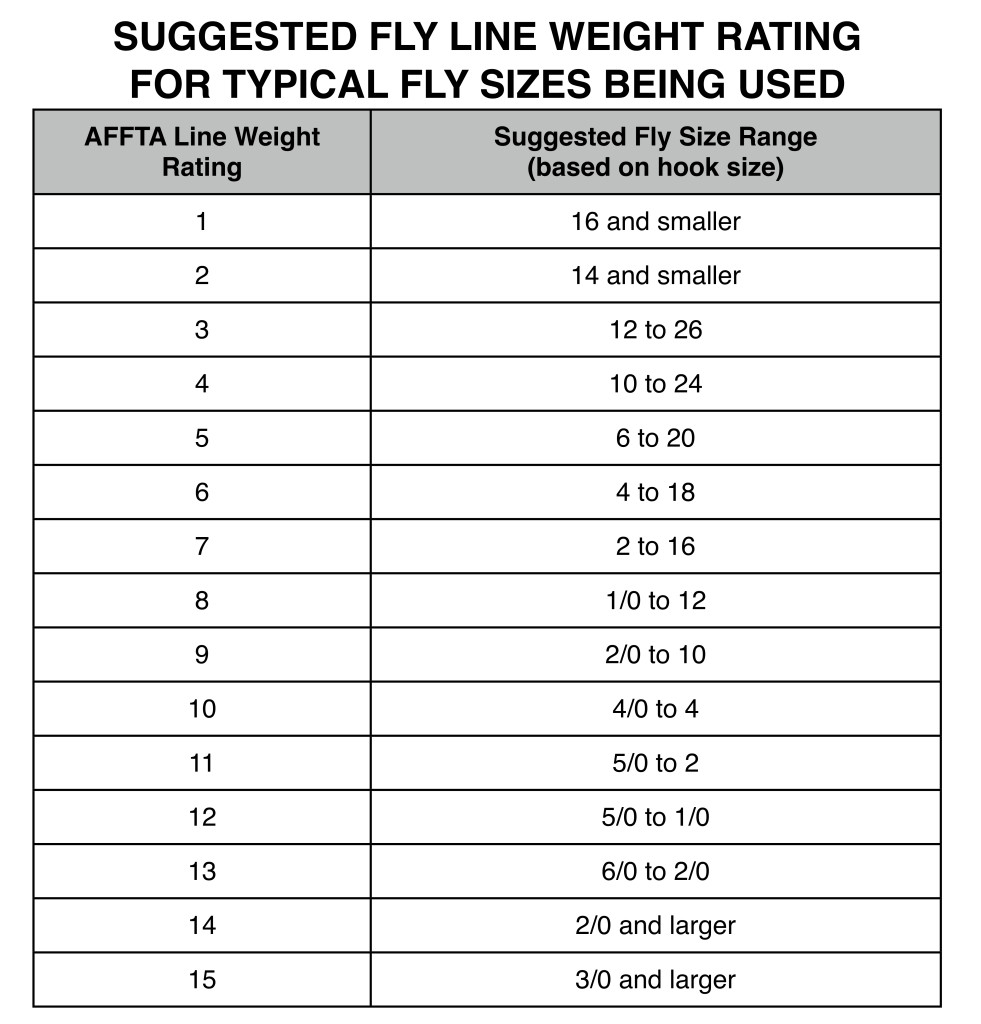

Fortunately for us, we don’t have to do all the math to calculate this, and can just look at a handy reference table to see what typical fly sizes correspond to an AFFTA line weight rating. And for those of you that haven’t educated yourself on hook sizes, remember this: Hook sizes are like fractions. The bigger the number, the smaller they are.

It should be noted that if you plan to add additional weight (multiple flies, split-shot, weighted flies, strike indicators, etc.) you need to take that additional weight into account and move to a heavier line weight, as the table does not account for that additional load on the line. I personally don’t consider such things, (or even line weights above a 7) as I’m a dry fly fishermen and have no use for them. I’ve simply included that information here in an attempt to provide a complete reference table.

Furthermore, (and this does apply to a dry fly fisherman) if you will typically fish where you will experience adverse environmental conditions (strong wind for example) it may require additional line mass to combat their affects on line performance, and using a heavier line than otherwise indicated in the table may be warranted.

So now, without really any bias or opinion entering into the equation (as of yet), another big variable has been decided: The fly line weight rating. As you can see from the table, it may not be a five-weight, and more than one line weight may be appropriate for the flies you’ll typically use. Your opinion of which of those to choose is just as valid as anyone else’s, so choose the one you want, and pay no attention to those that tell you otherwise.

Once you have the fly line weight rating selected, things tend to get a bit more “opinionated.” But there are still a few things left that can be decided, or at least narrowed down, by the physics associated with them. For example: Every reel, regardless of the size, has a finite capacity. In other words, it will only hold so much line. The thinner the line is, the more line length that reel can hold, and the opposite is also true. So if you are trying to put a 15 weight fly line on a tiny fly reel, you are likely to be very disappointed, as it simply won’t fit. Conversely, having a reel that is only half full with the entire line you’ve chosen doesn’t make much sense either, and adding miles of backing to fill that unused capacity just adds additional weight that you likely don’t want or need. So narrow your reel choices down to just those reels that have an appropriate capacity for the line weight you’ve selected, and all the top reel manufacturers provide the reel capacity information for you.

From there however you will find all sorts of opinions on which reel is “best”. But if you’ve done your homework and narrowed your options down as suggested above, a quality reel (Abel, Bauer, Hardy, Orvis, Ross, Sage, etc.) of any design or drag system will likely fill any need you will have. Which means your opinion is really the only one that matters if you’ve addressed the reel capacity issue appropriately.

Another law of physics that applies to the reel is gravity. Or in other words, how heavy is the reel? In some cases a heavier reel may be wanted, in other cases it may not. But consider that you can usually easily add weight to a light reel, but making any reel lighter is another matter altogether. So I’ll go out on a limb here, and state that, in my opinion, a lighter reel is easier to balance with a rod. Now before I go into any further elaboration on that point, let’s consider the rod, and then we’ll come back to it.

Fly rods are what most anglers place their focus on when purchasing new gear, (especially new fly fishermen) and they are also where it often becomes considerably more difficult to differentiate between opinions and facts. Emotions often run high and there are many more “distractions” that personalize and influence how an individual feels about this particular piece of equipment. So it’s easy to get caught up in a “this is better than that” debate, when in fact, both sides of the debate may be right for those particular individuals. Once again, we want to remove opinion as much as we can from the equation, and look at the facts in narrowing down the rod choices.

Here is a fact: A rod designer has certain criteria they are trying to fill with each rod they create, and they have an intended purpose (application) in mind when doing so. As such, most (if not all) rods produced today will have a recommended line weight rating for the rod. This is the suggested AFFTA line weight rating that the manufacturer/designer intended the rod to be used with in the application the fly rod was designed for, (or at the very least, with 30 feet of fly line being cast). In other words, they (the Designer of the rod) is of the opinion that in a particular application, line weight “X” will provide the optimum performance with that rod.

Uh-oh… There is that “opinion” word again. But yes, it is true. Just because the Designer/Manufacturer designed the rod for a particular purpose doesn’t mean that everyone that purchases that rod will employ it for the intended purpose, or in the environment (small stream, large still-water, etc.) that it was envisioned and designed to be used in. Nor does it mean that the designer’s opinion on how a rod should feel and perform in that application is the only correct opinion. (And it certainly doesn’t mean that their opinion should or will correspond with yours.) Hence the reason one manufacturer’s rods will appeal to certain segments of the fly fishing population, and why so many fly fishermen are brand loyal and try to convince others that Brand X rods are the best. In truth, they simply agree with the manufacturer’s opinion on how a rod should feel, and so (for them) the line weight rating is accurate and they love those particular rods. Others will not share that opinion and will prefer the way a different manufacturer’s rods feel.

Just remember that the “recommended” line rating for any rod is just that, a recommendation from the manufacturer. It’s very good place to start, and I caution you from deviating from it until you are more experienced. By casting various rods with their recommended line before buying anything, you will literally get a feel for how different manufacturers approach their rod designs. Chances are you will find that you have your own preferences in how they feel and may even become a brand loyal fly fisherman yourself, and there is nothing wrong with that. (For my own personal biases and equipment preferences, see my post Who is The Dry Fly Guy?)

So cast some rods that have the recommended line weight rating that you have selected and see which one feels right for you. As a word of caution, recognize that it is easy to get caught up in the moment and some rods will be very aesthetically appealing and have higher end components etc. If you can afford this kind of luxury, by all means consider them. But I’d be wary of casting rods that are priced above your budget as comparisons because you may find that you’ll want to drastically exceed your budget. In this case, ignorance can be bliss, and with the quality and performance of today’s rods at all price points, it probably won’t take long for you to find a rod within your budget that “speaks to you”. When you do, you’ve found the rod to purchase.

Now for the final word on rods, I need to go back to my previous comment that “a lighter reel is easier to balance with a rod” and explain that just a little more fully.

Many anglers will talk about “balancing” a rod with a reel, and in general, they are talking about the butt end of the rod (where the reel is placed), and the tip end of the rod having an equal amount of weight in relationship to the fulcrum (the angler’s hand on the grip). The basic idea is that when the angler is holding the rod level (horizontally), it wants to stay there with neither the tip nor the butt feeling heavier and tipping it up or down. In reality, even if this balance is attained at some point, it’s a moving target and it won’t remain balanced. As line is pulled off the reel and extended towards the tip of the rod (and beyond), weight is being removed from the butt end, and added to the tip end. As line is reeled back in, the opposite occurs. Like I said, it’s a moving target, and therefore can’t be truly attained in a fishing situation unless you always keep the exact same amount of line out. (In which case you wouldn’t need a reel and it’s called “fixed line” fishing. Tenkara being one form of this.)

That being said, I believe there are some advantages in finding a sense of balance with a rod and reel. But please recognize that it isn’t a static thing, and again, your personal preferences will dictate what type of balance you actually prefer. Some like their rods to balance more tip heavy, others like them more butt heavy. Some just don’t care and none of them are “wrong”. In considering this though, you should also remember that the rod acts as a lever, with the mechanical advantage (leverage) on the tip side of the fulcrum. As such, the tip has more leverage than the butt, so the longer the rod is, the more leverage the tip end will have. Which also means, the longer the rod is, the heavier the reel can be to counter balance it. And that is a fact, not an opinion. Regardless, just shoot for something fairly balanced when the reel is loaded with a fly line and backing, and you won’t be too far off regardless of what kind of balance you ultimately decide you prefer. And if truly in doubt, have it balance “tip heavy” because you can always add weight to the reel if you need to. (Hence my previous comment/opinion that a lighter reel is easier to balance with a rod.)

Now let me say that the preceding narrative provides some of the basic facts as they apply to selecting your equipment, but it is not intended to replace the knowledgable individuals you can find in so many fly shops. These individuals are likely to be your best source for clear guidance on choosing equipment. Just remember they also have opinions and biases that may, or may not coincide with yours. So start with your flies. I know it may seem backwards to some of you, but it isn’t. The flies will dictate the line weight needed to efficiently cast them, and that in turn will dictate the variety of choices available to you in a fly rod and reel from your local fly shop. And within those available choices, opinion is likely the determining factor of what you should choose, and your opinion is truly the only one that matters. At least when it comes to choosing your own equipment.

~ DFG